Many Mamans: Art Mothers and Monstrous Practice by Sinéad Gleeson

INTRODUCTION TO THE SERIES: ART HISTORY IS A MOTHER

In the first week of lockdown, Verb Wellington Director Claire Mabey and Megan Dunn, Head of Audience & Engagement at City Gallery Wellington, met via Zoom and decided to publish an essay series about art. We wanted to read more writing about how art moves people; we wanted to read more moving writing about art. It might lead to an event one day, we thought. But what would our theme be? On one of Megan’s daily lockdown walks, a catchphrase popped into her head: ‘Art History Is a Mother.’ (It was partly a joke about the pratfalls of art history, its famous omissions, but it was also a play on the multiple uses of that much-maligned word ‘mother’— motherhood being a mantle used to dismantle and divide women artists.)

So, who are your art-historical mothers? Claire and Megan agreed to ask five essayists to take on this theme and bend it to their will. First in the series is Irish author Sinéad Gleeson, who was in Aotearoa for Verb Festival last year, speaking about her glittering first book Constellations.

Many Mamans: Art Mothers and Monstrous Practise by Sinéad Gleeson

Mainie Jellett Decoration 1923

To sit for a moment and contemplate my art mothers is a complicated thing. The question presents an endless list of artists who have changed my way of seeing. To summon them, it is necessary to engage with history and context: how I came to see the work, where it was displayed, how old I was. The art—or books, or music—encountered in our porous, formative years goes bone deep. Hundreds of works show up, all colour and form, so I focus on time, the specifics of a calendrical date, a year, a movement. In a gallery, there is always a white rectangle on a wall with a date blinking back, in a definitive, unfussy font …

Dublin, 1990

If I think of a space, I wind my way, hand over fist on the rope, back to the start. My school art teacher brought her students to the National Gallery of Ireland, an imposing building situated on one of Dublin’s most stately Georgian squares. It is all wooden floors, interconnecting rooms, and heavy gilt frames. Galleries have a reverence, a spatial, spiritual hush that has always reminded me of churches. Moving from one canonical work to another, transfixed by A Convent Garden, Brittany by William Leech and Paul Henry’s Achill fishermen, falling hard for the corporeal oils and ghostly faces that peopled Jack B. Yeats’s paintings. I would like to tell you that my fifteen-year-old self caustically noted the lack of women on the walls, but this may or may not be true. The feminism I learned later is more likely to provide the revisionist imposition of this detail, but the fact remains today that Yeats is the only artist in the gallery with an entire room to himself.

But on that first visit, I noticed work by a group of women, whose abstract styles overlapped. Mainie Jellett’s geometric figures, the still-life work of Evie Hone, Norah McGuinness’s boxy colours, and the playfulness of Nano Reid. (All of these artists, I note, were the first art postcards I bought and pinned to my wall.)

Jellett and Hone had grown up in wealthy, protestant families, and Hone was a descendent of the landscape painter Nathaniel Hone the Younger. Both women left Dublin for Paris in 1921 to study with the cubist painters André Lhote and, later, Albert Gleizes. It was not just a geographic departure, but a move away from a country that was in the middle of a bitter War of Independence. It was also an Ireland where women still couldn’t vote and female roles were very much rooted in the domestic—wife and mother. Away from Ireland, their horizons expanded, and both women found a formal expression in cubism. On her return in 1923, Jellett had one of her (now) most famous pieces, Decoration (1923), included in an exhibition by the Society of Dublin Painters. Like much of her work, it references the composition of religious paintings, specifically the Madonna and Child. Writer George ‘AE’ Russell wrote scathingly that Jellett was ‘a late victim to cubism in some subsection of this artistic malaria’ and described her work as ‘sub-human art’. Evie Hone and Jellett were close. Both were proponents of cubism and their canvases revelled in their abstraction and asymmetry. Jellett’s often contained a central point that all colour and shape emanate from, and colour itself, for her, had a spirituality of its own. Like Jellett, religion was important to Evie Hone and appears frequently in her work. There is sense that she was less sure of herself, or her artistic vocation. As a child she suffered paralysis, which affected her hands and left her with a limp. After Paris, Hone also spent two years in a Cornwall convent, intending to devote herself to a religious life, but left after hearing a voice tell her: ‘If you stay here you will lose me.’ By the 1930s, she moved away from painting towards stained glass and her first commissions were for church windows.

This was not an easy time to be a woman—even for those from the privileged upper classes. It was harder still to be a cubist, when the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA) preferred traditional, realist work. Along with other artists—including Norah McGuinness—Hone and Jellett established The Irish Exhibition of Living Art, to showcase the more experimental work they felt the RHA shunned. They are credited with introducing modern art to Ireland, while resisting cultural and artistic impositions of what art—or an artist—could be.

•

And what of the art mothers who were mothers themselves?

In Little Labors, Rivka Galchen writes of motherhood and writing, of how the intersection of parent and practitioner is complicated. She lists famous writers who are women and did not have children: Flannery O’Connor, Virginia Woolf, Jane Bowles, Iris Murdoch. Diametrically opposed, there’s the prolific Shirley Jackson, who had four children and wrote many books. When Jackson arrived at the hospital for the birth of her third child, she was asked what her occupation was. She said, ‘writer’, but the nurse taking down her info replied: ‘I’ll just put down ‘housewife.’

When painter Celia Paul gave birth to her son (fathered by Lucian Freud), her mother offered to look after the baby so that she could paint. Three weeks after he was born, Celia Paul returned to her London studio and began to work again. Of her son, she wrote:

I would like to give up everything for him. I would like all my ambition and all my desires to be drowned with me. But some contrary instinct is working in me at the same time: I must save myself too.

There are many mother makers, mother writers, mother artists, but prefixes are often reductive: ‘woman’–writer, ‘personal’–essay. Many artists choose art over motherhood, some combine both, but what these roles have in common is the level of commentary. The moral judgement of choosing one over the other, and the critique of the work that is produced by the presence—or absence—of being a mother.

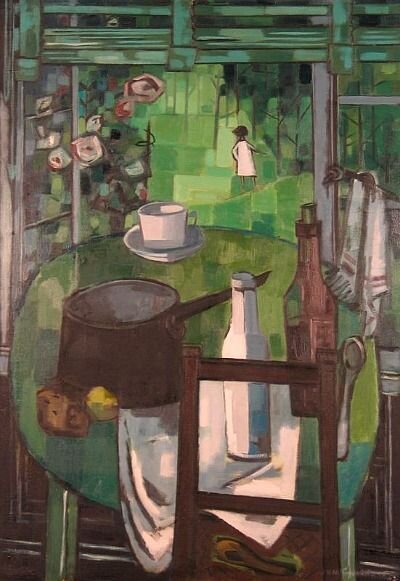

Norah McGuinness Garden Green 1962

Barbara Hepworth Blue and Green (Arthroplasty) 1947

Venice, 1950

1950 was the first year that Ireland participated at the Venice Biennale, then celebrating its twenty-fifth iteration. Several works by Nano Reid and Norah McGuinness were chosen, perhaps indicating that the Irish state was warming to less mainstream art. Reid’s work was expressionist, McGuinness’s more inherently cubist (her later 1962 work Garden Green is an incredible study in colour and perspective). Also showing at the Biennale that year was Barbara Hepworth, whose operating-theatre drawings of orthopaedic surgery fascinated me (and appear in my book Constellations). But Hepworth was first and foremost a sculptor and frequently felt as though she was in the shadow of Henry Moore. Both were from Yorkshire, attended the same art colleges, favoured direct-carving techniques and heavily influenced each other. At the Biennale, Hepworth was not happy with the pieces selected to represent her, claiming they were too ‘ladylike’, and doomed her to be ‘always be seen as the pupil of Moore’. Hepworth ploughed on, fearless with material—bronze, stone, wood—and always searching for some version of essentialism. She combined her art practice with raising four children, and never found there to be a conflict between motherhood and Jenny Offill’s ‘art monster’. Hepworth explained:

My studio was a jumble of children, rocks, sculptures, trees, importunate flowers, and washing.

Louise Bourgeois Maman 1999

Kara Walker Fons Americanus 2019

London, 2000

The Turbine Hall in Tate Modern is one of the most exhilarating spaces in art. Avowedly neutral, it demands capaciousness and sheer nerve—any artist engaging with the hall has to meets its expansiveness head on. It was here I saw Louise Bourgeois’s Maman, a giant spider sculpture, towering over the balcony of the gallery. It is initially, terrifying, all spindly steel legs at such elevation—but under its body is an egg sac, containing marble eggs, revealing its vulnerability. The spider spins webs, it is a creator—as mother and artist—and Bourgeois thought of this arachnid as a ‘repairer’. All of her work places the body at the centre, navigating domesticity, freedom, desire. Bourgeois had three children very close in age and worked until the week before her death, at ninety-one. She explained:

Spiders are friendly presences that eat mosquitoes. We know that mosquitoes spread diseases and are therefore unwanted. So, spiders are helpful and protective, just like my mother.

Earlier this year, in the same hall, I circled Kara Walker’s Fons Americanus. I didn’t know then it would be my last time gallery visit before lockdown. All that space, and the huge crowds, now feel like an anomaly. Walker’s large-scale fountain is based on the Queen Victoria memorial in front of Buckingham Palace, which Walker casually took picture of while passing in a taxi. The original structure is composed of imagery representing the British Empire, its colonial myth and its naval prowess. Walker’s fountain depicts carvings of lynching racial stereotypes and sea-faring slavers while sharks swim in the water below. It’s now feels oddly prophetic in light of the recent protests and conversations about race. Walker not only works as a reminder of profiting from suffering, but the dangers of monuments themselves.

In her 1971 essay, ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’, Linda Nochlin acknowledges ‘the very position of woman as an acknowledged outsider, the maverick “she” instead of the presumably neutral “one”’, and that the default artist is ‘the white-male-position-accepted-as-natural’. The authoritative voice is considered to be male; the ‘default’ artist or writer is also easily accepted as thus. Nochlin asks pertinently: ‘What if Picasso had been born a girl?’, wondering if his family—and his art-professor father—would have encouraged him so fiercely be an artist.

Cindy Sherman Untitled #462 2007-8

New York, 2012

The Internet is an amplifier: art, hate, movements. It is a lens and platform that has introduced us to artists, while teaching us about artificiality. It was where I encountered Cindy Sherman’s work, her deconstructions of identity, her dismantling of femininity in soccer moms, vamps, and society women. Serendipity struck when I found myself in New York for work with, not one, but two Sherman exhibitions showing: one in a small gallery in west Manhattan, the other a career-defining retrospective at MOMA. Sherman once said that a selfie is ‘a call for help’, no doubt, with her tongue glued to her cheek, which sounds like the kind of warped portrait she’d happily photograph. Her deconstruction of womanhood veers from sinister to comic, but her point about the vast spectrum of identity is unwavering.

The list of my art mothers grows. It becomes a matriarchy of names stitched together. Ana Mendieta, Paula Rego, Mainie Jellett, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Alice Maher, Tarsila do Amaral, Norah McGuinness, Yayoi Kusama, Leonora Carrington, Andrea Kowch, Mary Swanzy, Carolee Schneemann, Dora Maar, Aideen Barry, Gwendolyn Knight, Dorothy Cross, Judy Chicago, Evie Hone, Tamara de Lempicka. They are an ongoing repository of art mothers.

Their canvases and sculptures swarm in my imagination, they fill the art books on my shelves. But it is not the same. I have been thinking about the all the desolate art—unvisited, ungazed at—behind the locked doors of galleries, full of Beckettian pause, waiting for audiences to return. When the lockdown is over, I will go back to the big rooms of the National Gallery and stand in front of Jellett’s Devotion. I might tell its talismanic angles about all the artists that came after, about the women from other countries who painted or sculpted, who created a space for themselves on the canvas, moulded their hearts into bronze, creating a unique, but collective story. They line up like mothers, or protesters, to form an extensive coven.